This is the fifth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

The first ten amendments to the Constitution – the Bill of Rights – were proposed in Congress and ratified by the necessary three-fourths of the states in less than three years, a speed of action that seems improbable, given the undeveloped state of travel and communications at the time and the lengthy process more recent amendments to the Constitution have undergone.

But the urgency with which the new nation acted upon the Bill of Rights simply confirms this key point: the secular covenant by which the citizens of the United States agreed to be governed consists of both the Constitution document delivered to the country by the Constitutional Convention, and the Ten Amendments that comprise the Bill of Rights proposed by the Congress and ratified by the States.

There were four distinct phases in the formation of this secular covenant, or “solemn agreement,” and had not all four phases been completed, the agreement might not have held.

(1) The Constitutional Convention held in Philadelphia over four months between May 14, 1787 and September 17, 1787 that created the Constitution document, which would give Americans “a republic, if you can keep it,” as Benjamin Franklin told Mrs. Powel.

(2) The State ratification conventions, beginning on November 20, 1788, when the first such gathering convened in Pennsylvania, until the formation of the new country with the ratification by the ninth state, New Hampshire, on June 24, 1788, but continuing on to the ratification by the thirteenth state, Rhode Island, in 1790.

(3) The proposal of nineteen amendments and a new preamble, by James Madison, the representative from Virginia’s Fifth Congressional District to the newly formed House of Representatives on June 8, 1789, and debates that led to the passage of twelve of those amendments by Congress on a two-thirds vote, as the new Constitution proscribed, for presentation to the states for ratification as The Bill of Rights, on September 25, 1789.

(4) The ratification of ten of those twelve amendments, which we call the Bill of Rights, by the state legislatures of the requisite 3/4 states, a process that started when the New Jersey state legislature ratified all ten amendment on November 20, 1789 and ended when the Virginia state legislature ratified the all ten amendment on December 15, 1791.

It is our good fortune that the Founding Fathers were able to complete all four phases, thus cementing the bond that holds us together as a country today.

But for awhile there, it was touch and go.

To understand why, we need to understand what the Americans who chose to be governed by this “solemn agreement” or “secular covenant” understood the terms of that agreement to be.

We’ve combined two words with which you may be familiar, but whose specific definitions may not be at the forefront of your thoughts, to describe agreement formed by the Constitution and the Bill of Rights: “Secular” and “covenant.”

The first use of the word “covenant” is found in the Old Testament. Dictionary.com defines that Biblical meaning as “the agreement between God and the ancient Israelites, in which God promised to protect them if they kept His law and were faithful to Him.”

For those of you familiar with the Old Testament, that covenant usually refers to God’s agreement with Abraham (circa 2,300 B.C), and his subsequent agreement with Moses (circa 1,400 B.C.), in which the Ten Commandments were delivered.

Another definition of covenant, one that would have resonated with 18th century Americans, calls it “a solemn agreement between the members of a church to act together in harmony with the precepts of the gospel.”

The New England states–Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut in particular–were founded as colonies in the 17th century built around congregations of Christian churches, each of which had its own solemn agreement among its members.

Dictionary.com defines“secular” as “of or relating to worldly things or to things that are not regarded as religious, spiritual, or sacred.”

Putting those two together, we can define the secular covenant of the Constitution as “a solemn agreement between the states, and the citizens of those states, to form a government guided by the foundational principles of Federalism and the Separation of Powers as defined in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.”

Another important element of an agreement–and especially a solemn agreement like this secular covenant– is this: it must be freely entered into by all parties.

And that was the issue facing the newly formed United States after the first two phases had been completed and the Constitution was ratified. Without a Bill of Rights as they believed they had been promised in the Massachusetts Compromise, the Anti-Federalists–as well as a great number of Americans who may not have specifically given themselves a label one way or the other at the time–would not freely enter into the agreement.

While it was true that a new government was formed when New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution, the short-lived government of the United States under the Articles of Confederation had begun to unravel when the Philadelphia convention was called in 1787 ostensibly to simply “improve upon” that arrangement.

Lacking a Bill of Rights–amendments to be proposed by the first Congress–an Article V of the new Constitution offered the states another mechanism for introducing those amendments should the first Congress fail to act.

“The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments,” Article V of the Constitution began.

If two-thirds of the states–and there were only eleven on board at the time, so that meant only eight needed to agree–called for yet another convention, who knew where that might end up?

Many Federalists wanted to define this agreement as one that was completely operational after the second of these two phases–the ratification of the Constitution by nine states–was completed in June of 1788.

You may recall that back in February 1788, the Constitution was ratified by the sixth state-Massachusetts-only after the Massachusetts Compromise proposed by John Hancock and supported by Samuel Adams–was accepted by the ratifying convention in Boston. The delegates agreed to ratify the Constitution without amendments on the promise of the Federalists that immediately after it was ratified amendments constituting a Bill of Rights would be proposed, sent to the states, and ratified.

That compromise was championed by delegates to ratifying conventions in New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York, who ratified the Constitution.

Now, in the fall of 1788 with the new government formed and in the process of organizing, it was time for the Federalists to deliver on that promise.

And if they failed to deliver, one of the leading Anti-Federalists in the country, Virginia’s Patrick Henry, was determined to hold them to account.

Henry was famous for his pre-Revolutionary War oratory.

In 1765, he introduced the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions to the colony’s House of Burgesses. He reportedly said ” “Caesar had his Brutus; Charles the First his Cromwell; and George the Third ….may he profit by their example. If this be treason, make the most of it!”

Ten years later, in a speech to the Second Virginia Convention in St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia on March 23, 1775, he delivered another barn burner.

“Give me liberty, or give me death!” those who were in attendance quoted him as saying that day.

A leading Anti-Federalist, he was bitterly disappointed when the Virginia Ratifying Convention approved the new Constitution in June 1788.

But the new nation had been formed, and Henry had a role to play in where it went next.

It is interesting to note that the process of ratifying an amendment to the Constitution had a slightly higher bar than did the process of ratifying the Constitution itself.

Article VII of the Constitution simply said “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.”

Since there were only thirteen states at the time, that meant that the Constitution could be ratified with the support of 69 percent–or nine–of those states.

Article V of the Constitution stated that amendments proposed by either the Congress or an Article V convention “shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress;”

Ten states out of the original thirteen (77 percent) had to ratify an amendment to exceed the three-fourth standard in Article V for it to become part of the Constitution.

A former governor of the state, Henry was by far the most powerful member of the Virginia state legislature when it convened in the fall of 1789 to elect two United States Senators and draw up the state’s ten Congressional Districts to elect members of the new House of Representatives.

“His influence over the legislature was so evident that George Washington observed that ‘He has only to say let this be Law–and it is Law,’ ” Professor Richard Labunski wrote in his 2006 book, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights .

Henry used that influence in two ways to damage the ambitions of James Madison.

First, he ensured that Madison was not elected to the U.S. Senate by the Virginia Assembly. Second, he gerrymandered the Fifth Congressional District, which included Orange County, where Madison’s Montpelier residence was located, and recruited a strong Anti-Federalist candidate, James Monroe, to run against him in the elections scheduled for the following February.

Then, to add insult to injury, on November 14, 1788, barely five months after the new government had been formed, Henry made sure the Virginia Assembly passed a petition to the soon-to-be-elected first Congress to hold an Article V convention, although there language did not specifically mention Article V:

We do, therefore, in behalf of our constituents, in the most earnest and solemn manner, make this application to Congress, that a convention be immediately called, of deputies from the several States, with full power to take into consideration the defects of the constitution that have been suggested by the State Conventions, and report such amendments thereto as they find best suited to promote our common interests, and secure to ourselves and our latest posterity the great and unalienable rights of mankind.”

On February 5, 1789, the state legislature of New York passed its own Article V petition to Congress, and Federalists worried that more states might join them.

Anti-Federalists in several other state legislatures–particularly in Massachusetts and other states that ratified after the Massachusetts Compromise was proposed, like New Hampshire–were poised to pass their own Article V petitions.

Madison learned of Henry’s gerrymandering and the challenge by Monroe a few weeks later in New York City, where he was serving as a delegate to the soon to be dissolved Confederation Congress.

He hated campaigning, and debated for some time whether he should make the arduous journey back to Virginia to electioneer for his seat. After several friends back home wrote that Monroe presented a serious challenge, he reluctantly packed his bags and headed south.

The diminutive Madison, who stood barely 5 foot 4, and the towering Monroe, who stood just more than 6 foot tall, were friends despite their differing political philosophies at the time.

The two had purchased 1,000 acres of land together in upstate New York several years earlier, a speculative real estate venture. When Monroe got into financial trouble, Madison bought his interest out at a fair price. He later sold the land at a modest profit.

Madison had arrived back in Montpelier in late December, and campaigning across the wide expanse of the new Congressional District–which included Amherst County in the south west of the state, Culpeper County in the north of the state, Goochland County in the center, and Orange, Spottsylvania, Fluvanna, Louisa, and Albemarle Counties in between–began in early January.

“Madison would have a very difficult five weeks ahead of him,” Labunski wrote.

“Patrick Henry had done an extraordinary job of creating a congressional district in the Piedmont area of central Virginia that would be hostile to Madison and his supporters,” he added.

In mid January, “Madison and Monroe traveled together to Culpeper to address a Lutheran congregation. . . On January 26 [they] spoke together to citizens in Orange, the county seat of Orange County. [At the end of January they] spoke to ‘a nest of Dutchmen’ at what is today the Hebron Church in present day Madison County,” Labunski noted.

Along the campaign trail that wintry January, Madison “offered what amounted to a campaign pledge that if he was elected he would sponsor a bill of rights and work diligently towards its passage,” Labunski added:

Several groups in the district needed to be assured that Madison was genuinely committed to working for a bill of rights. Baptists, who would play a crucial role in the election, wanted Madison’s pledge that he believed an amendment protecting religious freedom was necessary and he would work towards its approval in Congress.

In the end, Madison’s diligence paid off. He defeated Monroe on election day, February 2, 1789 1,308 votes to 972 votes. Forty-four percent of eligible voters turned out.

The new Congress convened in New York City on April 1, 1789, but Madison took his time to carefully prepare his Bill of Rights proposal so he could present it at the right time.

One month into the new Congress, Virginia Rep. Bland presented the Virginia Assembly’s Article V Convention petition to the Congress on May 5, 1789 and asked that a committee take it uncer consideration. more than a month after it had convened.

Madison noted that “he had no doubt but the the House was inclined to treat the present application with respect, but he doubted the propriety of committing it [to a committee of the House] because it would seem to imply that the House had a right to deliberate upon the subject. This he believed was not the case until two-thirds of the State Legislatures concurred in such application, and then it is out of the power of Congress to decline complying,” the Annals of Congress reported.

Finally, one month later, on June 8, 1789, Madison proposed his nineteen amendments and new preamble to the House of Representatives.

The preamble was quickly discarded, and after three months of debate and deliberation, both the House and Senate passed twelve proposed amendments for consideration by the states for ratification.

One noticeable thing happened during this period of debate: Federalists seemed to soften in their opposition to the Bill of Rights, and many opinions on both sides changed.

A month and a half later, meeting in the port city of Perth Amboy, the New Jersey state legislature became the first to ratify all ten amendments of the Bill of Rights on November 20, 1789.

By June 7, 1790, nine states – New Jersey, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island — had ratified all ten amendments in the Bill of Rights.

In four states–Virginia, Connecticut, Georgia, and Massachusetts–ratification of the Bill of Rights languished.

When Vermont joined the Union as the fourteenth state on March 4, 1791, the three-fourth required to ratify the ten amendments that comprised the Bill of Rights jumped from 10 states to 11 states.

By November, Vermont ratified all ten amendment, but the deficit of one state remained.

Once again, Patrick Henry’s Virginia became the focal point, this time for the final battle.

“A less formidable and determined foe than Patrick Henry would have given up by now,” Professor Richard Labunski wrote.

“But Henry was not through. Having failed to obtain the radical amendments he had long demanded, he would do everything he could to prevent Virginia from approving the Bill of Rights. He told Senator Richard Henry Lee that the proposed amendments ‘will tend to injure rather than serve the Cause of Liberty,’ and he believed they were intended to ‘lull Suspicion totally on this Subject,’ to prevent changing the ‘exorbitancy of Power granted away by the Constitution from the People,’ Labunski added.

Henry had succeeded in delaying a vote on ratification on the Bill of Rights in the Virginia Assembly in 1789, but now, two years later, in the fall of 1791 with only one state needed to make it part of the Constitution, it was on the agenda again.

Though still influential, Henry was not a member of either the House or the Senate, now, so his spell binding oratory was limited in its effectiveness.

Finally, four and a half years after the Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia in May 1787, and two years, six months, and seven days after James Madison first proposed the amendments that became the Bill of Rights in Congress, the secular covenant that formed the Constitution and the Bill of Rights was finally sealed.

APPENDIX

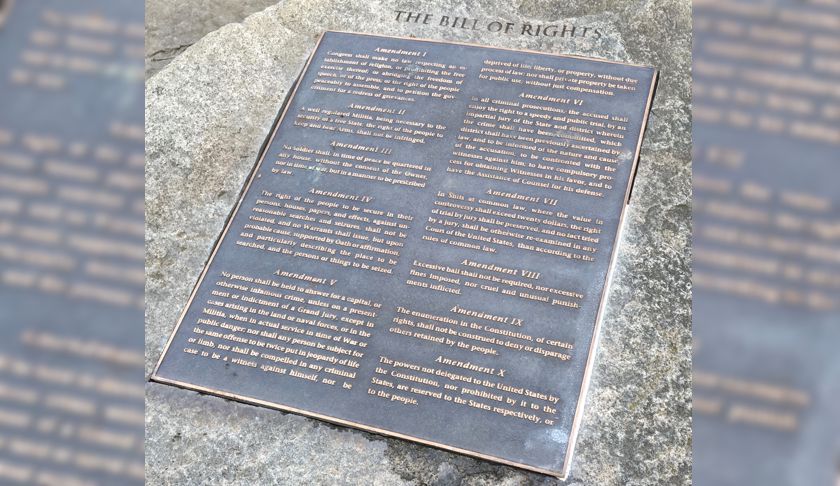

Here are those first ten amendments, the Bill of Rights, as ratified on December 15, 1791:

First Amendment

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Second Amendment

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Third Amendment

No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Fourth Amendment

The right of the People to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Fifth Amendment

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Sixth Amendment

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.

Seventh Amendment

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by Jury shall be preserved, and no fact, tried by a Jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Eighth Amendment

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Ninth Amendment

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Tenth Amendment

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

It took more than 200 years for the eleventh proposed amendment to be ratified as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment. That finally happened on May 5, 1992, when Missouri became the 38th of the 50 states that formed the United States by then to reach the requisite three-fourths required for ratification.

Twenty-Seventh Amendment

No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.

How this eleventh amendment proposed by Congress in 1791 ultimately became the 27th Amendment to the Constitution is quite a story.

“In 1982, a college undergraduate student, Gregory Watson, discovered that the proposed amendment could still be ratified and started a grassroots campaign. Watson was also an aide to Texas state senator Ric Williamson,” the Constitution Center reported:

Shortly after the amendment was ratified a decade later, New York Law School professor Richard B. Bernstein traced the journey from 1789 to 1992 in a Fordham Law Review article. Bernstein called Watson the “step-father” of the 27th Amendment. Watson was a sophomore at the University of Texas-Austin in 1982 and he needed a topic for a government course. Watson researched what became the 27th Amendment and found that six states had ratified it by 1792, and then there was little activity about it.

Watson concluded that the amendment could still be ratified, because Congress had never stipulated a time limit for states to consider it for ratification. Watson’s professor gave him a C for the paper, calling the whole idea a “dead letter” issue and saying it would never become part of the Constitution. “The professor gave me a C on the paper. When I protested she said I had not convinced her the amendment was still pending,” Watson told USA Today back in 1992.

Undeterred, Watson started a self-financed campaign to get the amendment ratified. He wrote letters to state officials, and the amendment was ratified in Maine in 1983 and Colorado in 1984. The story appeared a magazine called State Legislatures, and an official from Wyoming, reading the magazine, confirmed his state had ratified the amendment, too, six years earlier.

In 2017, the same teacher who gave Watson a “C” on his paper in 1982, petitioned the University of Texas to change it to an “A+.”

The twelfth amendment passed by Congress in 1789 and sent to the states for ratification has never reached the requisite three-fourths state approvals for ratification.

Unratified Amendment Proposed by Congress in 1789

After the first enumeration required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred; after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor more than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons.

[…] Download Image More @ tennesseestar.com […]

If you found this interesting, you should check out the Convention of States Project. http://www.cosaction.com/?recruiter_id=1584249